Robin Stryker, a 2016-17 CASBS fellow, is professor of sociology at the University of Arizona.

With a collaborator, she just published “From Legal Doctrine to Social Transformation? Comparing Voting Rights, Equal Employment Opportunity and Fair Housing Legislation,” in the American Journal of Sociology. During her fellowship year Robin was in study #4 – the same study occupied by her father, sociologist Sheldon Stryker, a pioneer of identity theory – during his 1986-87 CASBS fellowship year. Robin was able to tell her father that she was going to be a CASBS fellow a couple of months before he passed away in May 2016 at the age of 91. Pretty poignant…

The father-daughter connection through CASBS and the same study space was a no-brainer for a Q&A session. To allow for a little more perspective, we waited a bit and sat down with Robin in May 2017, toward the tail-end of her fellowship.

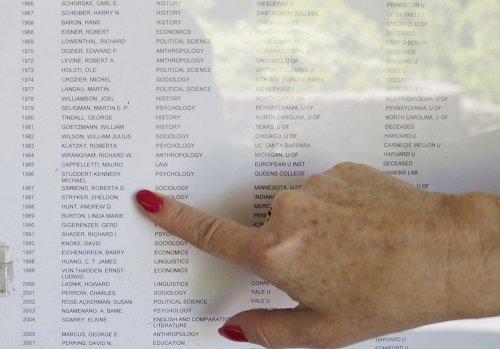

[Editor's note: Each CASBS study displays a "Ghosts in the Study" report outside its door, listing information about fellows who inhabited that study since CASBS's founding in 1954. Below, in the top photo, we see Robin Stryker, with her name placard displayed above study #4's Ghosts in the Study report. In the bottom photo, we see a close-up of Robin pointing to the Sheldon Stryker entry in her study's "ghost" report.]

CASBS: It’s a round number: 30. How has it felt being in the same study as your dad, exactly 30 years later?

Robin Stryker: It’s very bittersweet to be here. I’m glad he knew that I was coming because he was, I think, more excited about it than I was. And I was delighted.

It’s also been a bit sad and frustrating, because almost every day I have some kind of interaction, or something happens that I’d like to tell him about. Of course, he would be very excited about the ‘emotions study group’ that formed here this year. In fact, what is our group talking about tomorrow? Self-identity and affect. It stems directly from my dad’s work.

He was traveling until a couple of months before he died. He probably would have come out here and hung-out for a while, and absolutely would have loved meeting everyone and talking with them. I think it’s partly why I converted some of my time here to moving more into the areas where he was working, as well as the project I planned all along.

When my dad died I heard from several people, including for example, Woody Powell, who was a young scholar and CASBS fellow [in 1986-87], while my dad was more a senior scholar. Woody wrote to me, “It was so great being out here with your dad. He took time to listen to me; we talked about a lot of things. I still remember it." It was sweet of him.

C: What do you remember your dad saying about his year here? His CASBS experience?

RS: He loved it. For him, the year spent at the Center was highly significant; kind of a major highlight for him and his professional academic activities.

The year he was out here happened to be my first year as an assistant professor, which is why I was too hysterical to come out here and visit! But he repeatedly told me there were two things I just had to do. One was spend a year at CASBS. The other is go to the Bellagio Center, part of the Rockefeller Foundation, on Lake Como, Italy. You get gigs for a month. It’s lovely. I still haven’t applied to go to Bellagio. On my “to do” list.

Anyway, the CASBS year was intellectually rejuvenating for him. After years of too much administrative stuff he got back into the rhythm of really writing. He also loved the sense of collective purpose that came from a group dynamic. As we know, he was part of the [seven-member] special group on “Affect, Cognition, and Self” that submitted a group summary [published in the 1987 CASBS annual report]. That format, merging a bunch of sociologists and psychologists, was exciting to him.

He liked a social group format too. I get the sense that he, my mom, [1986-87 fellow] Otto Larsen, and his wife spent a ton of time on the golf course!

C: OK, so near the end of your dad’s life you two, at long last, collaborated on an article, “Does Mead’s Framework Remain Sound?” a chapter in the edited volume New Directions in Identity Theory and Research [Oxford Univ. Press, 2016]. During your career you deliberately had been avoiding your dad’s line of research. You wanted to make your mark as a sociologist and not…

RS: …not be derivative of daddy. The piece, on George Herbert Mead and classical sociological theory, confronts whether Mead’s original framework is consistent with all the advances in the social and behavioral sciences since the original texts. My dad had used those texts to develop his own identity theory, and other sociological psychologists took off from there. So the piece essentially is dad’s understanding of then and my understanding of now woven together. What I was really trying to do was move beyond social psychology and get people working in the sociology of culture, sociology of law, and sociology of organizations to read it and begin to think about how it could apply to what they do. If that happens, that would be amazingly wonderful.

C: What made the timing right for you two to collaborate?

RS: I had been developing my ideas and sharing them with him over many years. He wanted to start using some material I developed on the cognitive revolution’s implications for evolutionary theory. I said, “Sure, you give me credit, you can use it.” So he gave a big talk and everybody said to him, “You’ve got to write this up!” He didn’t do that, but he started saying to me, repeatedly, “You need to write this up,” and I would never do it. Finally, he volunteered me without my knowledge. The people putting together the book, and series of conferences on which the book is based, said to him, “What do you want to do for us?” Dad said, “I know what I want to do. I want to do this thing with Robin. So contact Robin.”

Then they contacted me and said, “Your dad volunteered you to do this piece. Will you do it?” I wasn’t going to say no…

By that time I was well established, so it wasn’t a problem to do it.

C: But you ran away from your dad’s stuff early-on.

RS: Yes. But here’s a funny story. For my very first paper as an undergraduate, in an introductory sociology class, I was fascinated by the Attica prison riots and wanted to figure-out: Who are these people? How did they interact? How did this escalate? I thought I needed a conceptual framework to think about the process of escalation to disaster. I went to the library and found some stuff on roles and identities that was useful.

So I wrote this paper about evolving definitions of the situations in self-other interactions, and I got an A+ on it. I took it home to my dad during the winter break, showed it to him, and he started laughing. I said, “Why are you laughing? That’s not nice! Look, the professor says I’m a born sociologist!”

He looked at me, cocked his eyebrows and said, “When you were in the library, did you happen to find anything written by your Old Man?” I said, “No, why, should I have?” I had no what idea what he did in the discipline. At that point, I began to learn. Then I made a very conscious decision not to go that route and instead did other stuff for a long time.

C: Even though you clearly were interested in it.

RS: Even though, from the get-go, clearly, I was interested.

C: Do you think the experience of your one collaboration with your dad held the promise for more collaborations, had he lived longer?

RS: Oh definitely, definitely. He was working on a number of things in-process with a colleague who I’ve become come close to over the years. We’ve talked about working together on some of that stuff, and in the end dad will have an ancillary hand in it.

C: Is there anything that you’re working on now that has echoes of your dad, that references his work?

RS: Yes. I’ll tell you about one that ties into the discussion a bunch of CASBS fellows had early on Election Day. Were you there?

C: Yes.

RS: I spoke about results of a pilot study I did with a University of Arizona student population on incivility in politics and the media. Building on that, I wrote a national survey that will be fielded over the next couple of months. In that survey, I incorporated specific questions about the importance of one’s partisan political identity. There’s a whole series of questions that will link aspects of political identity to the phenomenon of various aspects of political polarization. Ideological polarization. Affective polarization. The questions are foundationally based on identity theory. Now it moves into political identities, which my dad didn’t do very much with, but it’s taking the foundational concepts and creating measures for relationships between identity, incivility, and polarization.

C: I see the sweater of your dad’s that you keep here in the study. You must like that visible reminder of his presence? How does it help?

RS: I can tell you that every day when I come in, the days when I’m not writing that book that is my main project out here, I hear him saying, “Finish that damn book!” Part of the reason I’ve stuck his sweater over there, in a more visible place, these last few weeks, is to remind me to work very hard. And I have been. I’m writing actual text of actual chapters of the book. And I look over periodically at the sweater and I say, “See, dad, I am, you know? The damn book is getting done.”

By the way, my mother also is saying, “What?! You couldn’t have finished while I was still alive?!”

C: The familial guilt side of motivation.

RS: Yes…